Martyn Crucefix reads the opening lines of his poem 'Cargo of Limbs'. The book is available here.

LOOKING BEYOND PARADISE

Like love, a full, clear sense of our own context draws us away from the dangerous illusions of the absolute. In making judgements, in giving voice as writers, we ought always to say where we are coming from because – especially in these months of lockdown – we are having to re-negotiate our relationships with the world. On a daily basis, we are being caught in a paradox of distancing and a sense of community that may take us by surprise; a consciousness of our similarities and differences with others is even more important.

This is relativism writ large and it has long been part of my sense of self, more pretentiously, my credo. So when introducing Cargo of Limbs, my poem about the refugee crisis in the Mediterranean (an on-going crisis, though reports of it have been side-lined by virus-related news) I wanted to detail its origins: in 2016 I had been listening to a reading of Seamus Heaney’s translation of Book 6 of Virgil’s Aeneid. This is the book in which Aeneas journeys into the Underworld but, rather than the River Acheron and the spirits of the dead, the lines conjured up – at that time – the distant Mediterranean coastline I was seeing every day on my TV screen: desperate people fleeing their war-torn countries.

Some context: living in north London, I am more usually surrounded by an invisible fug and racket of noise from traffic, public transport, aircraft, people going about their daily business; of course, now all stopped. Even in such a unrelievedly urban landscape, I am noticing the birdsong about the house. For days on end I have no need of coins in my pocket. And yesterday, taking photographs of the apple blossoms emerging on the tiny tree in the corner of my garden – an area of twenty gardens backing onto each other and suddenly spookily quiet – I felt more than usually unselfconscious.

More context: last night we watched Location Location Location. The editorial angle was about a woman (looking to move house in Bristol) who had a PhD in something scientific. The commentary implied she was constitutionally going to find moving house difficult because she thought a lot and felt too little. Phil Spencer: ‘Too much analysis leads to paralysis’. She accepted this and garnered praise as she laid aside her intellectualising nature and began to feel more, felt less apart, particularly walking into a prospective property.

Likewise, within this house and – luckily – garden, I feel myself becoming a part, more embedded, partaking of a microcosmic landscape of noises, odours, light shifts, temperature changes that previously would have been swiftly interrupted (to spend money, earn money, to meet someone, drive somewhere). This week I have been mostly watching the apple blossoms slowly fill, break and open from their green buds. I take their picture. And promptly am ‘apart’ again – because photography is quintessentially the outsider’s view, the acquisitive view.

In 1977, Susan Sontag argued “to photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge – and therefore like power”. I capture the blossom. And – though not my intention – I feel more powerful because of it. There are so many more photographs being posted on social media – a friend of mine is posting daily ‘beautiful things’; the National Trust has been running #blossomwatch; Alastair Campbell is posting images of particular trees on his morning walks. Who can blame us. We want to feel a bit more powerful towards a world that has turned suddenly, bewilderingly, as if viciously upon us.

Beyond feeling helpless, what do writers do in a crisis? I think of Shelley hearing news of the Manchester Massacre from his seclusion in Italy in 1822; Whitman’s close-up hospital journals and poems during the American Civil War; Edward Thomas hearing grass rustling on his helmet in the trenches near Ficheux; Ahkmatova’s painfully clear-sighted stoicism in Leningrad in the 1930s; MacNeice’s montage of “neither final nor balanced” thoughts in his ‘Autumn Journal’ of 1938; Carolyn Forche witnessing events in 1970s El Salvador; Heaney’s re-location and reinvention of himself as “an inner émigré, grown long-haired / And thoughtful” in 1975; Brian Turner’s raw responses to his experience as a US soldier in Iraq in 2003.

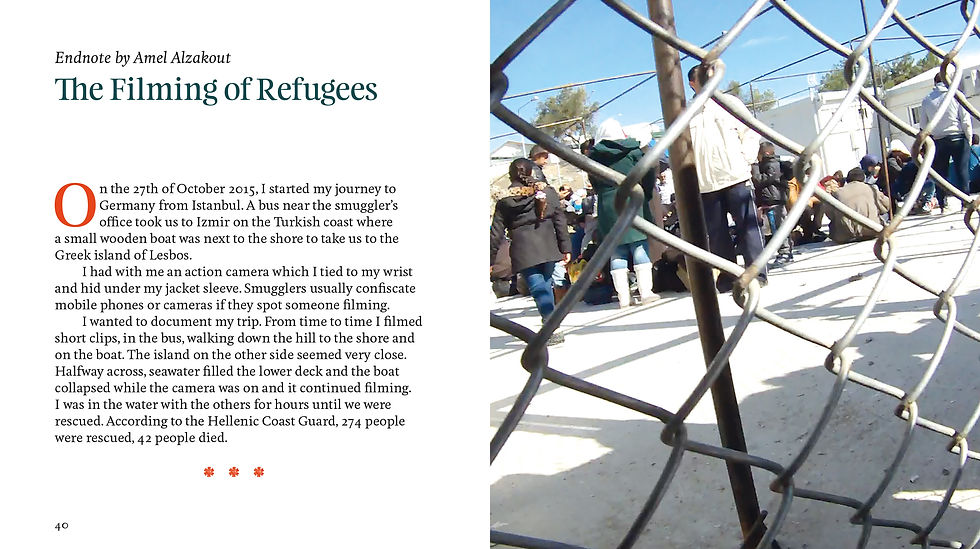

One of the film stills by Amel Alzakout illustrating 'Cargo of Limbs'. See below for more information

All crises differ but these writers were all wrestling with the opposing poles of witnessing and taking part, with finding their way around Sontag’s overly absolutist view: “the person who intervenes cannot record, the person who is recording cannot intervene”. Of course, we want to do both. But the current lockdown is dividing us along lines of those who must remain apart and those who are a part. And in one of those wholly unforeseen ironies of the historical moment, this is precisely the moral issue under debate in my Cargo of Limbs, between two journalists covering the refugee crisis.

One is a photojournalist who values and preserves his objectivity, his outsider status, remembering and admiring Ernest Hemingway’s 1937 reports from war-torn Madrid:

[…] let me file

untroubled as I’m able

to emulate a brother

sprinting the Gran Via

dodging smacks of snipers

let me not blink

at what rises towards me

His partner, Andras is a print journalist, a writer, who gradually succumbs to a sense of involvement as the horror and suffering of so many displaced people become clear to him.

The poem closes with his intervention, an attempt to disrupt his partner’s cool distance. As I was writing, I read about Don McCullin (the great British photojournalist, celebrated in Carol Ann Duffy’s poem, ‘War Photographer’). He said he was less interested in the technicalities of the photographic process: "All you have to do in photography is get the exposure right and then adjust your camera". But he added: "What you have to do is to adjust your mind, your emotions." Here’s a link to a BBC documentary in which McCullin speaks of witnessing an old woman in great danger during the Cyprus Civil War in 1964. Having taken one photo of her, he put down his camera and bodily picked the woman up and carried her to safety (see here). This is the sort of intervention I imagine at the end of Cargo of Limbs.

The strangeness of our current situation is that there is now a government edict against most of us becoming a part. Stay at home to save lives. On our little urban street, everybody emerges at 8pm on Thursday evenings to applaud the effort and sacrifice of key workers. No doubt, many of us have donated on-line to the National Emergencies Trust Coronavirus Appeal. But most other domestic commercial transactions are being conducted on-line or with contactless cards. I’ve no cause to carry cash and we will never do so in the same way again once this is all over.

The absence of those jangling coins in my pocket – that vanished sound of adult masculinity – is a sign of a change but too early yet to say of what kind. Will we emerge more distanced from each other after all this – will we forget how to converse? Or will the horrors of the present moment suggest that we ought to be revising the criteria by which we live, by which we are to be governed? I believe we should speak out from where we find ourselves, knowing others live differently. Together we will make a new kind of more inclusive, more compassionate chorus than the one we have heard too much of in recent years.

The film Purple Sea, directed by Amel Alzakout (whose images appear in Cargo of Limbs) and Khaled Abdulwahed, will celebrate its international première as part of the online edition of the 51st Visions du Réel festival. The films of the International Feature Film Competition will be accessible from the festival's website between 25 April and 2 May 2020, limited to 500 virtual seats per film.

Links to recent reviews of Cargo of Limbs:

Sheenagh Pugh: https://sheenaghpugh.livejournal.com/136445.html

Emma Lee in The High Window: https://thehighwindowpress.com/2020/04/14/reviews-of-recent-chapbooks-by-louise-warren-carole-bromley-martyn-crucefix-and-mike-barlow/

Ian Brinton in Tears in the Fence: https://tearsinthefence.com/2020/03/24/cargo-of-limbs-by-martyn-crucefix-introduction-by-choman-hardi-photographed-by-amel-alzakout-hercules-editions/

Martyn Crucefix's 'Cargo of Limbs' is available here

Comments